Buybacks don't benefit business

Arguments for them don't pass muster

Recent years have seen the shareholders of precious metals producers demand capital discipline to improve company balance sheets, and the return of excess cash, which several companies have been happy to undertake to attract investors, differentiate themselves from their competition and show they are serious businesses.

As many chief executives lament their declining share price over recent quarters despite gold prices being relatively high, the number of share buybacks through normal course issuer bids (NCIBs) is increasing. An NCIB typically authorises a company to purchase and cancel up to 10% of its issued and outstanding shares in the year the NCIB is active.

At face value, a buyback has a lot going for it: if a company believes its stock is undervalued, a buyback allows it to use its excess cash—variably defined as the cash left over after budgeted expenses, sustaining capital and exploration—to buy its stock in the open market.

With stocks underperforming the metal, it is arguably a good time to buy one's stock. Recent months have seen SSR Mining, SilverCrest Metals, Osisko Gold Royalties, Agnico Eagle Mines, Kinross Gold, Dundee Precious Metals, Eldorado Gold, Endeavour Mining, Karara Resources, O3 Mining, Calibre Mining and Mako Mining commence or renew NCIBs. Two of the most active companies in October were Eldorado and Dundee.

Eldorado spent more than $2 million buying back 160,000 shares, and Dundee spent a similar amount to buy back more than 250,000 shares.

Managers argue that by reducing the number of shares outstanding in this way, the business's earnings (and its value) are spread over fewer shares, so each share commands a higher price and the EPS (earnings per share) increases. That is the theory, at least.

Repurchase programmes are often introduced when share prices have seemingly cratered, leading companies to cite instilling confidence as a reason for buying back shares. Leaving aside the fact that management's perception of its own company's value is often inflated and at variance with that of the market, if management wants to instil confidence, wouldn't it better achieve that by spending its own money buying stock rather than the company's? "It seems odd that evacuating cash from the balance sheet would bolster the assurance of shareholders," mineral economist Alex Godell told Mining Journal.

Are buybacks a good investment?

In April, Fortuna Advisors published an in-depth analysis of buybacks by 360 companies across all sectors between 2018 and 2022, in which it highlighted that the buyback trigger is usually cash availability rather than a robust fundamental business case. "Many make buyback decisions based on excess cash availability rather than determining whether it's a good time for buybacks," it said.

During Barrick Gold's September quarter earnings conference call in early November, chief executive Mark Bristow was asked repeatedly about shareholder returns. Its policy is linked to it excess cash position and is for dividends or buybacks. In 2023, dividends are winning out, but in 2022 it also included buybacks.

He observed that its 2022 share repurchases were not triggered because the company's shares were undervalued per se, as were most of his competitors, but because the company believed they were even more undervalued than its competitors. "We saw relative weakness in our stock price compared to other companies in 2022, and when we see an opportunity, and we have free cash, we will buy [our stock] back. ... However, when the market goes against you, you have no friends. All the stock buying will never help you," said Bristow.

Timing is tricky to get right at the best of times. Even novice investors learn not to catch the falling knife of share prices when the market drops. The shares you think are cheap today will all too often be even cheaper tomorrow. Fortuna said most companies time their buybacks poorly, evidenced by a negative median buyback effectiveness in most years. "This suggests that few managements consider their companies' intrinsic share price when making buyback decisions. … Historically, most companies overlook the importance of timing and relative valuation when determining their buyback plans.

A good time seems to be when there is a clear trigger where the market responds negatively to news and management believes its share price has fallen too much. This was a stimulus to SilverCrest Metal's NCIB launch in August after its share price lost C$2 following the publication of an updated technical report on its Las Chispas silver mine in Mexico in late July. Its share price has since recovered somewhat, so any share repurchases made when it hit its lows were likely good business.

NCIBs are fundamentally defensive (giving away assets; what an odd defence!), and it seems many managements reach for them to prop their share price without a clear trigger (like SilverCrest) or where they see their valuation has fallen further or faster than their peers.

Measurement

Fortuna provides metrics to gauge the effectiveness of buybacks: Buyback ROI, calculated as an annualised internal rate of return (IRR) that accounts for the cash outflows associated with share repurchases, the estimated cash "inflows" of dividends "avoided"; and an estimated final "inflow" related to the final value of the accumulated shares repurchased. Another is total shareholder return (TSR) measured as the starting and ending average quarterly share price. "When a company repurchases shares, and its subsequent TSR is positive, it produces positive Buyback ROI. … In other words, the company earns a return on its buyback investment by retiring them before a market cap increase, which is concentrated in fewer shares," said Fortuna. When a company achieves a Buyback ROI that exceeds its TSR, it is called positive "Buyback Effectiveness."

Fortuna only included one miner in its list of 360, Newmont, which between 2018 and 2022 spent $1.7 billion in buybacks, achieved a Buyback ROI of 1.9%, yet a buyback effectiveness of -4.7%. This suggests gold miner buybacks are not good business. While Buyback ROI has not been calculated for the other miners mentioned in this article, the TSRs for their buyback programmes show high variability.

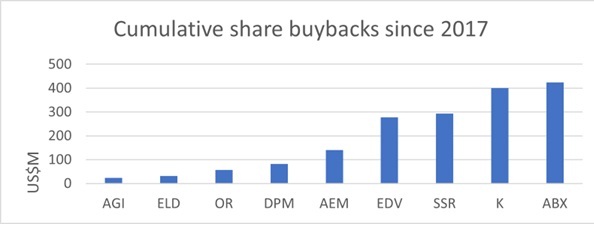

On this metric, Dundee has been the best performer; its share price has increased in all but one year that it has undertaken buybacks and spent $57.8 million in the process. At the other extreme is Kinross, whose share price has fallen yearly despite spending $400.8 million on buybacks. Alamos is also a strong performer, with positive TSR in all but one year of its buyback programme, and spending $23.6 million. Barrick's 2022 programme had a negative TSR after spending $424 million on buybacks. The results for Agnico, SSR, Endeavour and Eldorado have been variable and reflect how the broader moves in gold equities overpower the potential buyback benefits. SSR's TSR for 2023 is -22.5, Endeavour's is -17.5 and Agnico's is -6.

The data shows buybacks are inadequate in stopping share price decline, even in illiquid markets where buying or selling small packets of stock can have an outsized impact on a share price. Perhaps buying should occur when shares are on an upswing, in which case the additional purchase could help propel it higher, taking advantage of a moment when its stock is in demand.

Placebo

Precious metals miners are price takers, and the value of their businesses and share price movements depend significantly on the price of their underlying metal on external exchanges. As such, management would be better served to focus on efficient operations and an effective growth plan rather than spending cash on buybacks since the gold price is a much larger force than repurchasing a few million shares. Like it or not, the price of gold equities bobs up and down with the tidal surge of the gold market, so do NCIB purchases achieve their stated aims? Unsurprisingly, then, the data shows little evidence that buybacks are effective in anything other than draining treasury. A few million shares may be removed from circulation, but this has no impact on the value of a mining business, which is based on the metal price.

The earnings per share data of companies with NCIBs shows the same undulation with metals prices as non-NCIB companies, suggesting the nibbles they take out of their share count have no impact. "This is simply an adjustment that reallocates the company's market valuation over the new share count: the buyback does not grow the pie. The pie actually shrinks as cash exits the business," said Godell.

Few companies get anywhere near purchasing the 5-10% of their shares they are authorised to. Is the lack of effectiveness just poor implementation? If companies do not buy their full allotment each year, are they not giving the mechanism a chance to work?

Possibly, but companies also continue to issue shares, which suggests reducing share count is not such a priority after all. One of the few companies to fulfil its allotment is Eldorado Gold, which spent $17.7 million to buy 1.4 million shares in 2022, 0.8% of the 182.5 million outstanding at the time. Six months later, when it announced its next NCIB for 500,000 shares, its shares outstanding had increased to 202.8 million. "Since buybacks carry with them the prospect of future dilution, it must be pondered whether they are an inherently self-defeating mechanism," said Godell.

A twist to this though, is that buying back stock to achieve a higher share price only benefits a company's financial position if it subsequently issues new shares. "The company's market capitalisation may increase, but unless and until the company recapitalises through a share offering, the buyback cannot be considered a productive use of capital. A buyback's value to the company is null until it is crystallised," said Godell.

Shareholder returns?

Many companies state buyback expenditures under "funds returned to shareholders", which is a misnomer, as the recipient of buyback funds is no longer a shareholder. If a company wants to return excess cash to shareholders, many argue it should be done via dividends, as these reward an investor to stay invested, whereas buybacks reward investors to hit the exit. One imagines that B2Gold, which includes attributed gold production from its shareholding in Calibre Mining in its quarterly results, would rather see the junior pay a dividend than repurchase stock. It should be noted that the investors do not invest in gold companies for dividends, which have relatively low dividend yields compared with other sectors, so why do companies bother with returning capital at all?

One way in which dividends and buybacks are equal is that neither does anything to enhance the balance sheet: they are a decapitalisation that does nothing to improve a company's fundamentals. This point underlines one of the most controversial aspects of buybacks, particularly for companies that have long-term debt. Rather than engage in financial gymnastics, which may or may not benefit the business, management should perhaps retire debt. To put this into context, Barrick's $424 million in buybacks is equivalent to 8.9% of its current debt load; Kinross's $401 million spend is 16.8%, Endeavour's is 26.1% and SSR's would more than cancel its existing debt.

Fortuna believes buybacks can efficiently use excess cash when it cannot be profitably redeployed within the company. "Buybacks serve as an efficient method to distribute such excess return through the capital markets to other companies with better growth prospects," it said.

There is also an argument that if a company has too much cash on its balance sheet, it could become a takeover target. Buyback in this context seems to be a defensive mechanism for management, which may lose their jobs after not finding something profitable to do with excess cash, than shareholders, which may benefit from M&A action driving the share price higher.

Growth

Mining is a sector where assets are eventually exhausted, and new deposits need to be brought in and developed, which often means buying smaller companies, yet efforts to do this often backfire. The mining sector's checkered history of making splashy acquisitions at the top of the market and destroying value led investors to demand shareholder returns, in part arguing that if management has access to too much cash, it will do something ill-advised with it, like buy other companies or projects, or build mines. This suggests investors do not trust management, and if that is the case, why are they invested in a particular company? "It doesn't seem like a strong argument in favour of buybacks," Alex Godell told Mining Journal.

There is a serious point here as the mining sector is littered with acquisitions and mine builds destroying shareholder value. Both New Gold and IAMGOLD have had to sell assets due to cost overruns and other issues at their respective Rainy River and Cote gold mine developments, for example.

Even if a company's capital spend and exploration programmes are fully funded and there may not be a suitable acquisition opportunity currently available, doling out cash to shareholders would seem to be imprudent for a business that needs to continuously reinvest to remain a going concern. A critical difference between buying equity in another company versus your own is, "when one company acquires another, it spends cash and adds assets to its balance sheet in return. When a company repurchases its own shares, cash is spent, but no asset is obtained," said Godell.

It is also giving away the future ability to act. "Spending cash on a buyback today precludes spending that money on future opportunities. It is ‘opportunity opportunity cost'—forgoing the opportunity to capture future opportunities," said Godell.

The cyclical nature of metals and their price cycles behoves companies to hold onto cash for the inevitable day when prices fall, or there are unforeseen events that continuously happen to miners. Nothing sinks faster than the share price of an undercapitalised mining company, as IAMGOLD, New Gold and many others have experienced. "In a cyclical business like mining, producers may not have a consistent earnings base on which to rely, which increases the premium of having cash on the balance sheet," said Godell.

The October quarter results round illustrated this. Teck Resources was hit with more issues at its QB2 development in Chile, adding another $600 million to development costs; Newmont reported hairline fractures in the grinding mill's gears at Ahafo in Ghana, requiring replacement and lost production; and Agnico Eagle Mines had a transformer issue impact the semi-autogenous grinding mill at Detour Lake in Ontario, Canada resulted in unscheduled mill downtime.

The need for cash is even more poignant for non-cash-flowing exploration companies, particularly in a market in which it is challenging to raise in. Yet, O3 Mining recently, in October launched a NCIB to repurchase 5.4 million shares, which would cost it some C$7.5 million!

What's Your Reaction?